Will AI Replace Literature Reviews? History May Tell

As AI tools become mainstream and promises of generative AI loom, entire disciplines like literature review may be automated. But glimpsing into the past helps us realistically anticipate the future.

There’s a mixture of excitement and concern when it comes to how AI will revolutionize (or, more worryingly, replace) research. However, most discussions tend to be limited in focus, looking only at the next 20 or so years, without considering the bigger picture.

Scientific research has been pursued for millennia, and even the term research is 400 years old, stemming from the French, recherche, meaning “to search intensively”. Technologies throughout history have repeatedly revolutionized how research is done. By considering how these changes have happened in the past, we can look to the game-changing implications of AI with a broader perspective.

Here, we’ll look at literature reviews in particular, examining how they’ve evolved over time, and what the future may look like when most of the work can be done by AI.

Join us on May 29th for our Literature Review Webinar, where we’ll cover the best tips and tricks to accelerate your literature review using Litmaps.

Literature Reviews: Past

Literature reviews, as we know them, only started appearing in a more formalized format around the 19th and 20th centuries. Before that, scholars would discuss and cite other works, but generally didn’t share official “reviews” as a preface for their own work. For example, in the work of Hippocrates, an ancient Greek physician in the 4th century BCE, previous treatments and ideas were criticized but no specific texts cited.

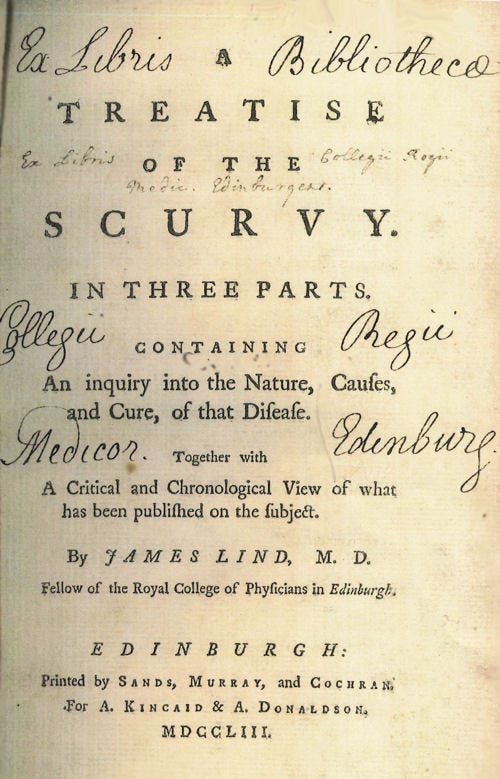

The first literature review

One of the earliest recordings of what we’d consider a modern day “literature review” is included in James Lind’s A treatise of the scurvy, published in 1753. At the time, the British Navy had been suffering from widespread issues with scurvy, and the causes were yet unknown. Lind recorded his clinical trials and potential cures, as well as “a critical and chronological view of what has been published on the subject”, i.e. a literature review.

“It became requisite to exhibit a full and impartial view of what had hitherto been published on the scurvy… before the subject could be set in a clear and proper light, it was necessary to remove a great deal of rubbish.” - James Lind, for his 1753 literature review

Although Lind tried his best, he appeared to still miss some sources. Later scholars pointed out how he overlooked “Woodall’s 1617 publication The Surgions Mate with its clear recommendation of equipping ships to the East Indies with lemon juice to prevent scurvy”.

This 18th century mistake is still seen today: Lind used only one “database”, the library at the Edinburgh College. Today, best practices still demand that researchers use several databases when conducting a literature review.

The first meta-analysis

Meta-analyses, a particular type of literature review which also involve conducting an analysis on the combined results of various studies, also date back to the 18th century. At that time, concerns over whether the smallpox vaccine caused more harm or good drove Thomas Nettleton, a doctor in West Yorkshire, to collect statistics on the mortality of the vaccine. Later, this data along with that collected from other sources, formed one of the first meta-analyses.

Literature reviews in the 20th century

By the 20th century, literature reviews were becoming more common. For example, Sigmund Freud’s 1905 book Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious acknowledges the state of the field in the introduction, and quotes other authors on the topic.

But how these reviews were conducted looked very different as compared to today. Researchers, whether students or senior researchers, would spend months poring over the available literature in their libraries. Barbara Tuchman, an eminent 20th century historian who examined what lead to World War I, surmised it as such:

“To a historian libraries are food, shelter, and even muse.” - Barbara Tuchman

These traditional and hugely time-consuming techniques of sifting through literature at libraries meant it was very easy to miss important and relevant work. Even Tuchman herself nearly missed out on a critical set of primary sources for one of her books; articles written specifically by the protagonist of her book:

“With no clue to their existence, I might never have found them [the articles], which would have been a serious omission for Stilwell’s biographer. This is the kind of thing that makes one shiver to think of what else one may be missing.” - Barbara Tuchman, 1981

Most students and researchers today would still acknowledge that missing sources still poses a challenge to contemporary literature reviews.

Literature Reviews: Present

Online databases and advanced search tools have radically transformed the literature review process for researchers. Instead of living out of libraries for weeks on end, researchers are able to conduct comprehensive searches in a matter of few hours. With the newest AI-driven tools, even reading these sources has been partially automated, so that each step of the research process is faster.

Instead of taking months to manually pore over books in libraries and weeks of reviewing the materials, it takes hours or even minutes to achieve each of these steps with modern tools (i.e. Litmaps).

The same goes for all the steps throughout the research process. Staying organized is now automated with reference managers and in-app tools (i.e. Tags in Litmaps). Double-checking for missed sources now comes down to taking a few minutes to re-run searches across databases and monitoring searches.

It’s worth noting that some researchers still rely on more traditional methods, despite the plethora of tools available. For example, historians relying on primary sources (like Tuchman’s example) may still need to do some research manually. Although libraries globally have invested in digitizing primary sources (i.e. those articles and 18th century literature reviews mentioned earlier), not all sources have been digitized. This library in Ireland documents what primary sources have been digitized, so researchers know what is and isn’t covered.

Literature Review: Future

Researchers today view AI as a promising technology to automate labor-intensive tasks in literature reviews, and, of course, research more broadly. Today’s tools already save researchers time in finding articles faster and reviewing relevant work, but it is perhaps only a matter of time until AI can automate the entire review process. AI isn’t yet at the level of reliability and quality necessary to replace researchers, but as technologies advance, it’s conceivable that such tools will make manual, human-written literature reviews obsolete.

In particular, this may make typical review articles less valuable. The kind and quality of the review will determine its value in a future AI-driven world. For example, systematic reviews and meta-analyses will continue to be valuable, because such reviews consider papers altogether, looking for potential biases, and surmising a new conclusion based on the combination of these works. The automation of such comprehensive studies may be a much longer way off.

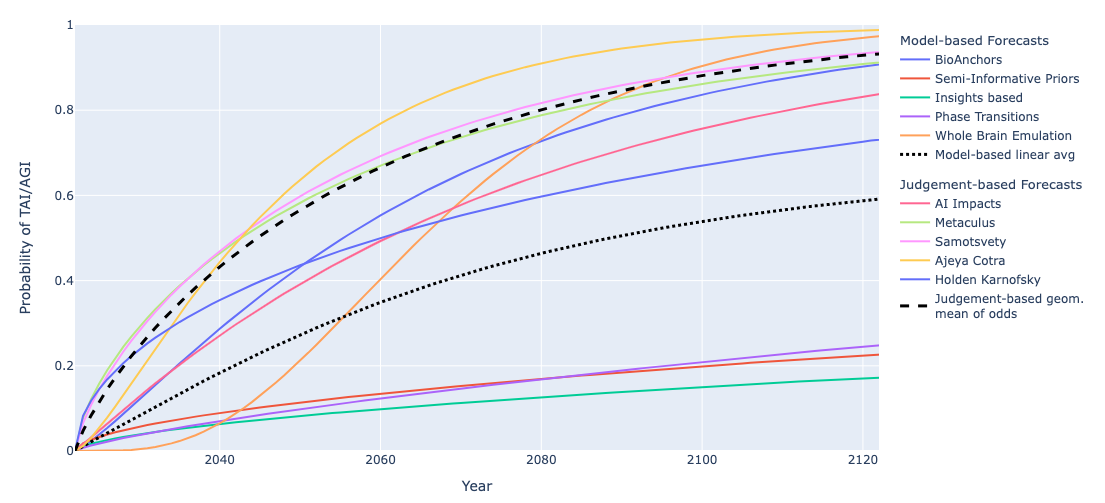

The strongest believers in AI envision how it will transform every aspect of scientific research, far beyond automating literature reviews. AI can change everything from experimentation and scientific development, to determining how research is funded or who gets tenure. The rate at which this occurs depends on the state of technology, society and their interaction.

Some scholars believe that by 2030, AI will be able to automate and tasks requiring “routine intelligence”, such as transportation, customer service, and marketing. Many aspects of the literature review process fall under that umbrella, like gathering sources, reviewing papers, and writing summaries. As for generative AI, which could conceivably write entire systematic reviews, the predictions are still 20-40 years in the future.

These predictions may sound intimidating, but of all the fields seeing automation, reviewers may be the most grateful to see this evolution. After all, the vast majority of reviews are conducted to set the stage and motivate research contributions. Automation here is likely a welcome change, enabling researchers to focus more on addressing research gaps and coming up with groundbreaking solutions.

The way research gets done has evolved dramatically over the centuries. AI may seem radically revolutionary, but it may be just as shocking as search databases were to scholars who had been conducting all reviews manually for most of human history. Even in a future dominated by fully-automated AI-generated reviews, it’s unlikely that the biggest issues, like missing sources, will simply vanish. When comparing today’s issues (like missing sources in a review), key problems and challenges persist despite new tech, and only change in how they manifest.

As such, it becomes more important to accurately identify those challenges and biases in order to effectively use AI to fix, rather than exacerbate, those issues. Otherwise, the past is bound to repeat itself.

How do you view the place of AI in the big picture of literature reviews throughout time? Is it solving old problems or making new ones? Share your thoughts with us below!

Resources

Integrating AI in academic research – Changing the paradigm April 2024

Rating the robots: Artificial intelligence for literature reviews March 2024

Systematic Reviews—From 1753 to Today June 2023

Reflections on the history of systematic reviews 2018

Thomas Nettleton and the dawn of quantitative assessments of the effects of medical interventions. 2010

"The vast majority of reviews are conducted to set the stage and motivate research contributions" is an unfortunate reality: Reviewing the literature never stops and has to be done at every level of the research with different goals: first the 'who' (purpose and authors' qualifications), the 'how' (method - reviewing how other people did it), the 'what' (reviewing what other people found out), and finally the 'why' (discussion - what do the results mean, if anything). The search techniques and places are of secondary importance, and because of the repetitive nature of the review, AI is well suited to help with automating the trivial parts of the process. There is also a class of literature reviews that are research papers in their own right, often produced by and for those trying to enter a field for the first time. AI can and will augment all of these systematic search and find activities from here on out but it is unlikely to be very useful as a fully autonomous agent. In practice, my (undergraduate computer and data science) students have the greatest difficulty with literature reviews - they just don't like to invest the time, and I get that. In my struggle to get them used to literature reviews, your Litmaps tool has been a god-send: it has boosted my students' literature review capabilities and motivation, and it has made their research much, much better - so thank you for that!

The past is not necessarily a good predictor of the future. Back before the invention of the steam engine, you could have predicted a stationary economy for the thousand years to come based on 2 millenia of zero growth/cap. This is not what happened.

AI has the potential to completely change our societies, rendering many jobs obsoletes. Historically new jobs have replaced old ones, but this is not an iron rule. It's an empirical rule over just two centuries of industrialization. Especially, as the evolution moves faster than any historical rate, and replaces intelligence as well as strength, we might not be able to adapt well enough.

Or at least, it's quite naïve to assert that there can be no first time in history.