ChatGPT for Research: Do's and Don'ts in 2024

ChatGPT, and AI tools in general, have evolved dramatically over the last year, as have their uses for scientific work. Here's what researchers should know about using these tools in 2024.

Just a year ago, we wrote our first Do’s and Don’ts for ChatGPT. Since then, a lot has changed. Many researchers have experiment with ChatGPT, and 30% of scientists have already used generative AI to write papers, according to a 2023 Nature survey. These tools are already transforming how science gets done, but what we’ve seen so far may be just the tip of the iceberg.

We recently interviewed Ilya Shabanov, creator of The Effortless Academic, to examine how AI tools like ChatGPT have evolved over the last year, and what role these tools do and should play in academia. Shabanov has been investigating academic tools over the last year, building a community of like-minded researchers through Twitter. He started by sharing his expertise in productive note-taking techniques and tool usage, but has since evolved to consider the wide range of technologies available to academics. Today, his platform, The Effortless Academic, gives considerable attention to using AI in research.

Here, we dive into what researchers need to know about using AI tools and ChatGPT in research today.

A new way to view AI tools

Since its inception at the end of 2022, ChatGPT has taken the world by storm, and scientific research along with it. The original problems that surfaced have mostly settled, only to be replaced by a new wave of concerns. The regulations across publishers and its banned use in peer review reflect this caution. However, many researchers are also optimistic. The majority of academics agree that generative AI will help researchers with repetitive tasks and reduce language barriers, which can radically improve research collaborations and opportunities worldwide.

If the scientific community’s reaction is mixed between extreme caution and hopeful, futuristic thinking, then Ilya Shabanov is somewhere in the middle: optimistic about the novel applications of AI in research, and distinctly aware of the key drawbacks and issues. He explores the world of AI-powered research, where new applications surface almost daily. According to him, there is no shortage of tools to explore, but only a fraction appear to provide genuine value: “Most tools are not very useful, but they’re easy to build, and since with AI you can build tools in a few days, we’ve seen many come and go. There’s a cambric explosion of tools (so to speak) but only a few tool families will evolve to see the light of day.”

The majority of tools and uses of generative AI (i.e. ChatGPT) focus on improving writing and reading. But Shabanov feels this is just the tip of the iceberg, and the most impactful uses of generative AI are still being overlooked.

The best use cases for researchers

Improving writing and evaluating written work are two of the most common uses of AI tools today, and are often central to the most heated debates, like if AI should be banned in peer review or how AI can reduce the trustworthiness and quality of scientific work.

Although improving writing and reading are no doubt useful, Shabanov feels these applications are limited in scope. The majority of the scientific community appears to be unaware of the fundamentally transformational applications available, which we dive into below.

Learn a new topic, as an expert

One of the most exciting uses of generative AI is the ability to quickly jump into a new field. This is equally salient for novice student researchers entering a field for the first time as it is for mature researchers learning a new domain. For Shabanov, the ability to jump into a new topic quickly and solve cross-domain questions is remarkable.

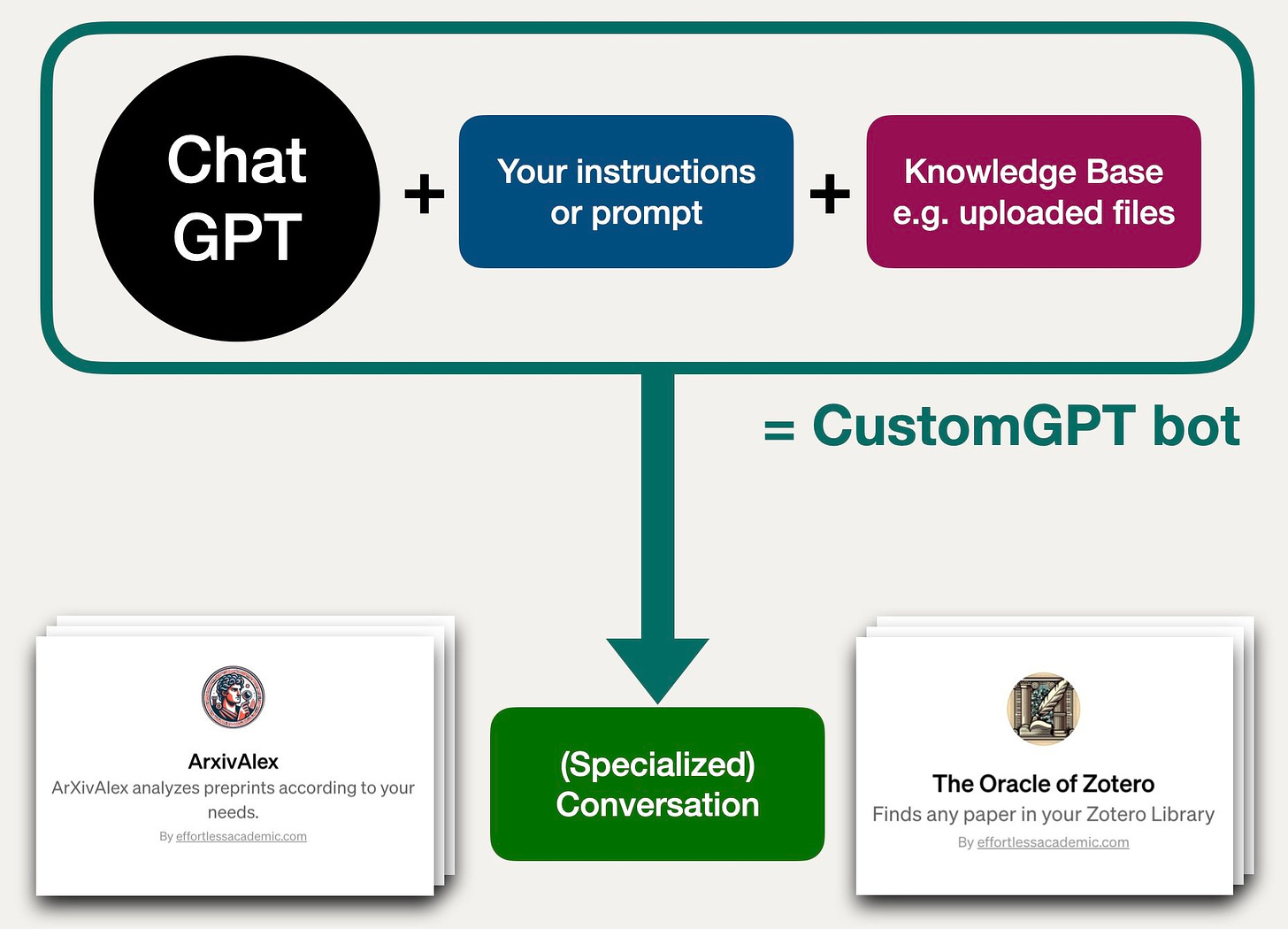

How to do this in practice varies based on use case. The most basic methods involve researchers interacting directly with ChatGPT and asking it questions. On the other end of the spectrum is custom GPTs, where users can train a personalized bot to answer any question on a topic, given a specific set of data. These AI bots can be given specific texts, books, papers, etc. to help them solve specific tasks better. For example, a bot can be trained to recommend the best statistical tests for your data. The key limiting factors when it comes to developing these assistants are the user’s creativity and “prompt literacy”.

“AI enables you to wedge into these cross-domain questions much faster… Before that, you’d have to read a couple books. No PhD student or let alone a professor has time for that.” - Ilya Shabanov

Fill knowledge gaps and find supporting evidence

AI tools are highly effective at helping researchers find resources and examples. This is particularly useful when trying to find supporting evidence or alternative approaches to a given method. For example, Shabanov recommends the prompt "find evidence for/against" for any document or text in order to critically analyze it from multiple perspectives (using Consensus). Note, this isn’t equally effective across all AI tools/bots. For example, Consensus, SciSpace and ScholarAI are expressly trained on millions of scientific papers, whereas the default ChatGPT is not.

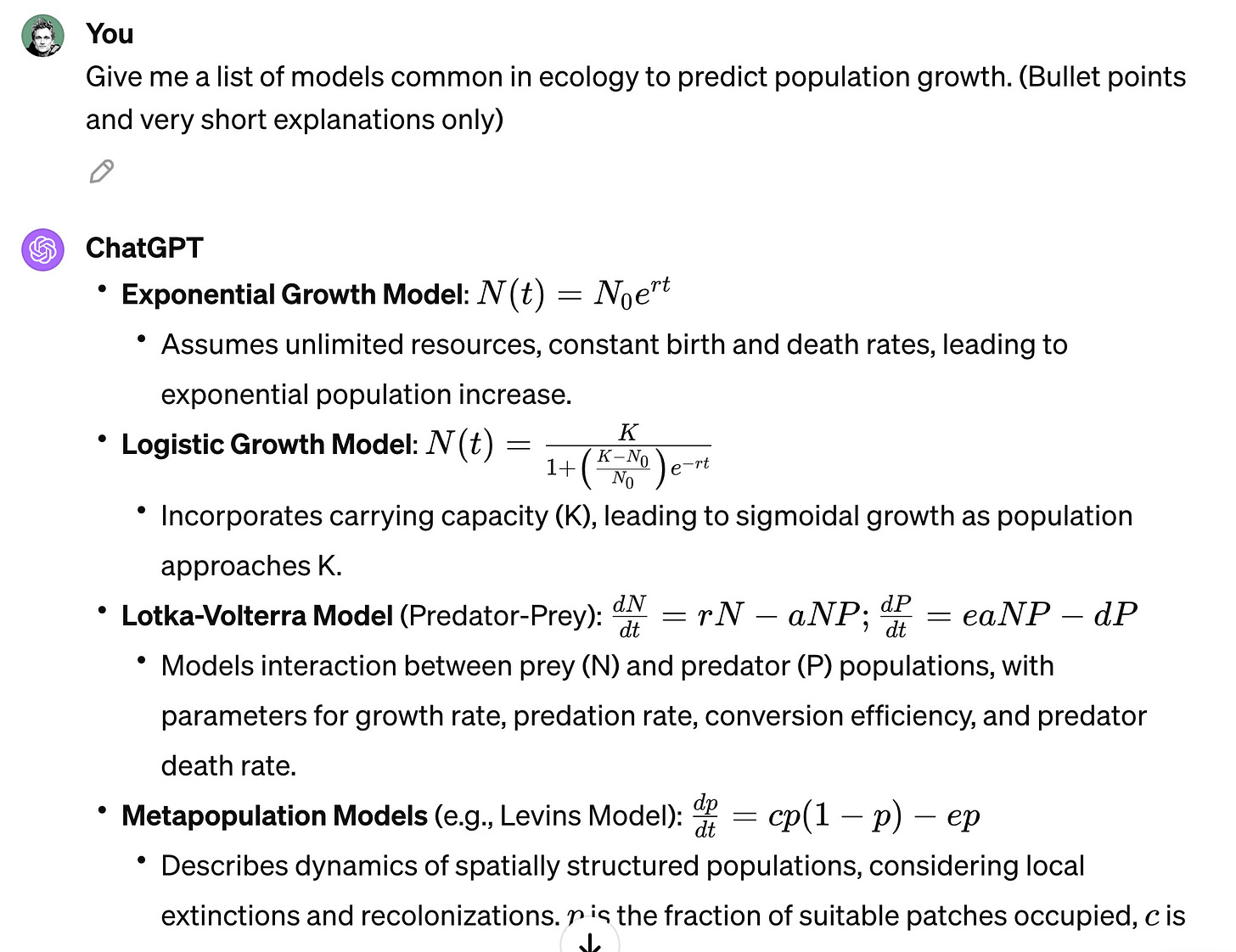

By leveraging AI’s ability to study large corpuses of information and learn facts, researchers can close gaps in knowledge more easily than manually searching. Shabanov cites an example in his field of ecology, to determine what models exist for predicting population growth. Although dozens of possible algorithms may exist, identifying all of these in the literature manually is an arduous process. Plus, a more novice researcher may not even know what to search for. Instead, he queries ChatGPT (see image below).

Here, ChatGPT provides the top algorithms, and serves as a starting point from which to dive deeper into each recommendation.

Writing

The majority of AI-assisted tools today focus primarily on helping researchers write better and faster. Scientific writing has clear, specific rules. AI can easily identify how text is written and adapt it to this style. Shabanov shares his techniques for using AI to help improve how one writes. For example, he may input a text and ask AI, based on certain rules of writing, where he could improve. In fact, AI could be treated like an initial peer reviewer, asked to review articles before they are even submitted.

However, it’s worth noting that the time-saving capabilities of these tools are often offset by paying additional penalties regarding the quality and reliability of the results. As Shabanov shares, “Since the technology isn’t highly reliable, I pay for that time through accuracy, which, in science, is often unacceptable.”

What to watch out for in ChatGPT, in 2024

Many researchers were initially skeptical about ChatGPT’s responses because of its hallucinations. Although the issue persists, it has improved significantly with ChatGPT-4, which has a significantly lower rate of hallucinations compared to 3.5 or Bard (according to some studies). This is particularly true when models are expressly trained on specific corpuses of knowledge. The community also appears to discuss this problem less often. As Shabanov shares, “In 2024, barely anyone talks about it [hallucinations], and there are ways around it. You have connections to the Internet, to scientific databases. The biggest thing is not hallucinations, the biggest thing is that it’s incomplete. That it misses certain things.”

Shabanov stresses that AI tools can serve as an effective starting point to dive into a new topic, but that the information cannot be assumed to be fully complete.

Most users today are already aware of the other key issues in AI models, like how they exhibit and exacerbate various biases. A 2023 study identified political biases in ChatGPT, and just a couple weeks ago Google’s Gemini AI came under fire for some generated images. This issue is particularly hard to solve, as we attempt to create perfect models using data from an imperfect world.

Poor results are one problem, but when these inaccuracies start to permeate the academic system, they become an even bigger issue. The community was in uproar after the image below was circulated: an inaccurate AI-generated image which wasn’t caught in peer-review and ended up in a published article. Researchers who specialize in assessing the reliability of scientific papers, like Elizabeth Bik, are especially cautious of these new technologies, fearing that “Generative AI will do serious harm to the quality, trustworthiness, and value of scientific papers.”

It’s essential to note that the limitations and disadvantages of AI tools vary greatly. Students, in particular, should be aware of AI tool limitations, since they are more likely to use free or limited versions, compared to their supervisors and colleagues who have access to better resources. For example, ChatGPT4 provides significantly better results than 3.5, but with its $20/month price-tag, many students can’t afford it.

Ideally, advisors and senior researchers take responsibility to ensure their students are educated in how to appropriately use these tools. But, they may also not know the answers themselves. This is where the variety of webinars and workshops available on these topics should be given consideration, as they provide a reliable way to stay up-to-date on the ever-evolving landscape of AI tools.

Although regulations about AI’s use in peer review and publication have been formed, the dust is still far from settling when it comes to the impact of AI in research. The scientific community is abuzz, with both avid supporters and cautious skeptics contributing to discussions. Some researchers, like Ilya Shabanov, are trying to shift the community’s perspective from one focused exclusively on the biases and inaccuracies of AI towards a more optimistic and inclusive view of how AI can support and accelerate research.

Shabanov believes these tools can radically transform how science gets done. He encourages researchers to start experimenting, explore the best use cases, and be creative. Although it’s tempting to ask ChatGPT to simply summarize a paper, there are far bigger fish to fry.

“Use it to leverage the knowledge it has and close the knowledge gaps that you have, finding these jigsaw puzzles pieces that fit into one another.” - Ilya Shabanov

Do you use AI in your research? Are you worried about the future of scientific research? Or excited? Share your thoughts with us below.

The Scoop would like to warmly thank Ilya Shabanov for his unique perspectives and valuable contributions to this edition of The Scoop. Learn more about his work on this topic at The Effortless Academic.

Resources

Is ChatGPT making scientists hyper-productive? The highs and lows of using AI Feb 28

A ridiculous AI-generated rat made it into a peer-reviewed journal Feb 16

AI hallucinations: The 3% problem no one can fix slows the AI juggernaut Feb 7

muy innovador