Future of AI Research in Industry vs Academia

Over the last 20 years, industry has gained the majority of resources and talent in AI research. New policies and funding support a future that enables both academia and industry to flourish together.

“Are you going to industry or academia?”

It’s common question discussed among Computer Science PhD students across the globe. And it’s being answered more than ever before with the response:

“Industry.”

Over the last 20 years, there’s been a gradual shift of resources and computing power into the private sector. The ability to work on bigger models with greater impact is attracting AI PhDs like never before. Not only does this impact the talent funnel into academic institutions, but increases the growing divide between the two sectors. Without the same sizeable reserves of funding and power, academic institutions are finding it more and more difficult to keep up. Without their contributions, AI initiatives focused on public interest also risk falling behind. Now, policymakers are responding to the burgeoning division by finding solutions that ensure public institutions can continue to play an essential role.

In this newsletter, we’re examining how AI research has shifted into the private sphere and the implications this has had for public interest. As policymakers meet to discuss new plans and universities respond strategically, actions are already underway to ensure academic AI research continues to flourish.

The resource imbalance between academia and industry

Given the monetary success of the tech industry, it’s unsurprising that the private sector has enormous investment capabilities in new technology. However, the true scale may still be shocking. Tech giants can pour billions of dollars into new AI models, whereas research institutions compete for million dollar grants. Take this example: in 2021, US government agencies invested $1.5 billion into AI research, while Alphabet spent $1.5 billion on DeepMind alone. In the same year, the global AI industry spent $340 billion (according to Ahmed et al. 2023).

But, it hasn’t been this way for long.

Up until the early 2000s, research was roughly uniformly pursued between academics and industry professionals in AI. In the last two decades, industry has gained the upper-hand in three key resources: talent, computing power and datasets.

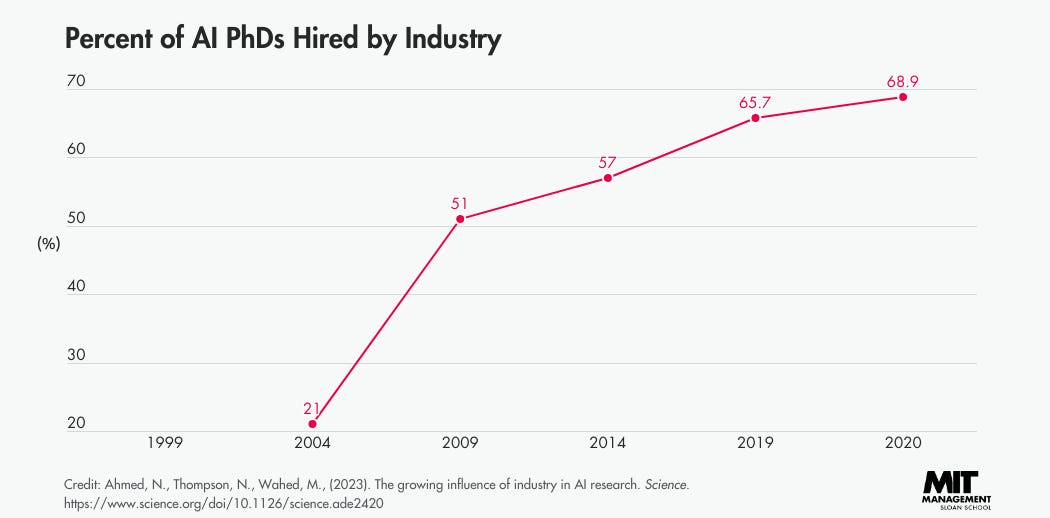

Since 2004, the rate of PhDs specialising in AI going into industry has increased more than eight-fold. In 2004, 21% of AI PhDs went into industry. As of 2020, it’s almost 70% — even higher than comparable engineering specialities. Naturally, where the talent is, innovation flourishes.

Industry has also gained a considerable advantage with computing power. As AI models grow bigger — handling more parameters and thus capable of greater achievements — so their power demands grow. For example, ChatGPT-3 has 175 billion parameters. These resources are just a matter of affordability, which most academic institutions don’t have the funds for.

So far, these divisions between industry and academia are challenging, although not altogether unique. The same exists across many other domains, such as bioinformatics. But there is an additional layer of distinction that is unique to AI and its development: emergent abilities. Simply put, some AI capabilities are only discovered when models are especially large. Academics with limited budgets and power can’t easily contribute to research in this area. Given that negative characteristics may also be amplified in large models (bias, toxicity, etc.), collaborations between academia and industry may be particularly valuable here.

In short, industry success enabled a positive cycle in accruing more of the resources needed for continued development. Although this has enabled enormous progress and transformation in the field, it’s come at some cost. Namely, the exodus of talent from academia to industry, making it harder for institutions to continue contributing effectively. This means the key contributions that academic projects focus on — those with public interest and societal good — may fall by the wayside.

This is why we turn to policymakers to establish better guidelines and regulations which secure resources for academics and ensure the ethical and beneficial application of AI.

What policies are levelling the field?

It’s vital that the playing field for AI research continues to include academic institutions. With public funding and mission-driven grants, academic projects are often held responsible for serving public interest. The key drivers are meaningful policies and regulations that support academic research and control for unethical AI.

Thankfully, there is no lack of organisations promoting “AI for good”. AlgorithmWatch focuses on protecting the rights of people and reducing bias. The Alan Turing Institute works with policymakers in the UK to make ethical choices when it comes to AI. The Institute for Ethical AI & Machine Learning, also in the UK, sets the standards for responsible AI deployment. The Ada Lovelace Institute is invested in promoting AI for public good, and even experiments with getting the public involved in commercial AI.

As vital as these initiatives are in the development of equitable AI, they still often leave academics behind. After all, what can close the resource gap between industry and academia? Some initiatives try to tackle this problem in particular.

In 2020, the U.S. formed the National AI Research Resource (NAIRR) task force. NAIRR needed to find out how to get the data and resources needed to support federally-funded AI projects. At the start of this year, they released their roadmap to help get academics the research infrastructure they need. It’s an exciting proposition to help provide the resources necessary, but with a sizeable downside: six years and $2.6 billion dollar request from a government that invested only $1.5 billion in AI in 2021.

So, how can academia invest in AI?

Academic institutions need better access to resources in order to contribute to AI research as effectively as industry. Given that policymakers take time — potentially years — to create effective programs, the best bet may be for institutions to respond themselves. By reallocating budgets, altering existing approaches to recruiting talent, and collaborating with industry, universities can take immediate action to better support their AI researchers.

Institutions can shift funds around to prioritise AI research. Across the U.S., new buildings are springing up across campuses to house new AI institutes and centres. U.S. universities are investing heavily in AI. The University of Southern California has invested more than $1 billion and Georgia Tech, $65 million. The NSF is investing $140 million distributed across 7 newly established National Artificial Intelligence Research Institutes (AI Institutes) across the U.S.

However, if the numbers previously discussed ($1.5 billion for DeepMind) are any testimony, even these numbers aren’t enough to compete with industry’s compute power. Thus, the nature of the problem should be approached not with a competitive lens, but one of collaboration. Computing power is easily won by collaborating with industry directly, as is already done on plenty of AI projects. For example, the University of Florida’s Research Computing centre partnered with NVIDIA, and already created the largest computer for AI in U.S. higher education. Collaborations like these, whether at the university or individual level, are one of the fastest ways to get resources to academics.

Institutions are already transforming how they recruit in order to keep AI talent. Universities are putting newfound effort into recruiting by making salaries more competitive and compelling prospective faculty by the potential impact they can have. Whether this will result in more inequality across departments, or bring everyone up together, remains to be seen.

Although the AI-research dilemma is challenging for academic institutions, it may also be just the push needed to help universities restructure and address other issues. For example, making academic positions more attractive for competitive candidates may mean rethinking how faculty are rewarded and supported. In turn, these change may lead to improvements across institutions.

What do you think of how academia is keeping up with AI research? Share with us your thoughts by commenting below or tweeting us @LitmapsApp.

Resources

Study: Industry now dominates AI research, May 2023

Colleges Race to Hire and Build Amid AI ‘Gold Rush’, May 2023

Global push to regulate artificial intelligence, plus other AI stories to read this month, May 2023

Google to work with Europe on stop-gap ‘AI Pact’, May 2023

OpenAI CEO tells Senate that he fears AI’s potential to manipulate views, May 2023

The EU and U.S. diverge on AI regulation: A transatlantic comparison and steps to alignment, April 2923

2023 State of AI in 14 Charts, April 2023

The growing influence of industry in AI research, March 2023

Emerging Non-European Monopolies in the Global AI Market, Future of Life, November 2022